【China Daily】2017: Change to what?

2017年1月3日

As a year of massive political shocks ends, and one whose outlines could not be more in doubt is just beginning

The world economy is likely to face many challenges in the year ahead, not least an extraordinary level of uncertainty.

United States President-elect Donald Trump takes the oath of office on Jan 20 and has promised protectionist measures against China and a program of fiscal expansion.

■ The Great Certainty: Uncertainty

Britain’s negotiations on quitting the European Union are likely to begin in the spring around the time of French presidential elections, both of which could have major implications for the future of the EU.

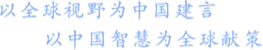

A worker at a car manufacturing plant in Zunyi, Guizhou province. The Chinese economy will struggle to maintain its momentum in 2017, economists say. Provided to China Daily

So where does this leave China? The world’s second-largest economy enjoyed a relatively benign 2016 with growth stabilizing at 6.7 percent in the first three quarters.

External events – not least the possible US tariffs on Chinese imports – could partly derail its economic progress.

The Chinese government made clear its own economic agenda at the Central Economic Work Conference, attended by senior leaders in Beijing, in December.

It set out six directions of policy: maintaining medium-to-high "new normal growth"; stability; supply-side reform; a new development concept focusing on innovation and the development of green technologies; improving quality and efficiency; and combining policies at both the macro and micro level that work for the good of the overall economy.

Vincent Chan, managing director and head of China research for Credit Suisse, who is based in Hong Kong, says that for the first three months of the year China will be trying to work out what the new policy agenda will be in the US.

"This is the major uncertainty. You have a situation where not just China but nobody else understands what this is going to be. Politics is going to be the big issue, which will influence the economics."

Chan, however, believes China’s growth, assuming no major external shocks, should increase to 6.8 percent in 2017, 0.1 percent up from the level achieved so far this year.

It will be notched upward by export growth of 8 percent, compared with the 6 percent contraction in goods and services sold overseas in 2016, he says.

"The current high levels of infrastructure investment at two and a half times the level of nominal GDP growth will keep the economy steady at 6.5 percent, and exports will give it an additional push next year."

Duncan Innes-Ker, regional director, Asia, of the Economist Intelligence Unit, based in London, says the Chinese economy will struggle to maintain its momentum in 2017. He believes growth will slow to 6.2 percent.

"What has driven growth in 2016, particularly in the second half, has been the construction sector, which has been related to the strength of the housing market," he says. (Property prices in the major cities have risen 30 percent over the year).

Innes-Ker believes the current credit growth of 20 percent a year, fueling debt, is becoming unsustainable.

He though thinks the government will wait until 2018 to tackle that, resulting in a hard landing, with growth slumping to 4 percent but recovering to 5 percent in 2019.

"If it doesn’t, there would be severe strains in the financial sector that would be very damaging in the longer term," he says.

Louis Kuijs, head of Asia for the global advisory firm Oxford Economics, who is based in Hong Kong, thinks there will be no major change in economic policy until after the 19th Congress of the Communist Party of China in November, when a new Standing Committee will be elected.

He believes policymakers will manage to achieve 6.3 percent growth.

"Growth will continue to rely on policy support in the form of fiscal expansion and, especially, generous credit growth. We do not expect policymakers to significantly slow the pace of credit expansion before the party meeting."

Edward Tse, founder and chief executive officer of the management consultancy Gao Feng Advisory, says he is not particularly worried about debt in the Chinese economy.

"It has never been proven what is a dangerous level of debt. I don’t think right now China is at any major risk."

Tse, also author of The China Strategy and who is confident the economy will enjoy growth of between 6 and 7 percent in 2017, believes debates about investment in infrastructure becoming increasingly inefficient in terms of return miss the point.

"I do not believe they take into account all the multiplier effects of having a highly efficient transport system. They might say a high-speed rail line from point A to B is not worth it, but they fail to see the benefit from the point of view of the whole rail grid being improved by the additional line," he says.

Chan at Credit Suisse says the main worry about China is not the industrial economy but the financial system, as evidenced by the weakening of the yuan. In the year to November it had depreciated by a trade-weighted 8 percent.

"It is a measure to some extent of how important the Chinese yuan has become as a global currency," Chan says. "I think it is less important than the US dollar or the euro, but now more significant than either the Japanese yen or the British pound.

"You can see this with market behavior over the past two months responding to the yen falling by 15 to 20 percent. There has been virtually no reaction. When the Chinese yuan falls by just 2 percent everybody seems to worry."

The currency depreciation reflects concerns over rising debt in the system, shadow banking and bond market weaknesses, he says.

"It goes further than just being a matter of the exchange rate itself."

One of the major concerns is whether Trump is serious about imposing trade barriers on Chinese goods, such as the 45 percent tariff on imports proposed during the election campaign.

On Dec 22 the president-elect sent an ominous signal by appointing Peter Navarro to the new post of director of trade and industrial policy. Navarro, a professor at the University of California, Irvine, has been highly critical of China.

Wang Huiyao, president and founder of the Center for China and Globalization (CCG)in Beijing, China’s largest independent think tank, believes the rhetoric seems to ignore the reality of a globalized world that relies on very sophisticated supply chains.

"This means that the iPhone is assembled in China and products sold by Walmart in the US are sourced from China. If we suddenly move away from this then consumers will be hurt – the very consumers who now seem set against globalization by voting for Trump and Brexit.

"We still live in a globalized world, and that is a fact. We sink or swim together."

Tse, who is acknowledged as one of China’s leading business experts, believes that instead of putting up barriers, the US could receive a jobs boost from Chinese manufacturing investment in the rust belt.

The Chinese automotive glass maker Fuyao opened a glass fabrication plant, which will be the world’s largest, in Moraine, Ohio, in October and created thousands of jobs.

"There is no reason why a Trump government should not welcome this kind of investment because it is not taking jobs from America but adding them," Tse says.

However, he says, he is picking up sentiment from businesses that because of the uncertainty they may prioritize investment in locations on China’s Belt and Road Initiative and not in the US or Europe.

"More Chinese companies are looking to identify opportunities away from Europe and the US and are looking to central Asia, Africa, Southeast Asia and, in particular, are showing renewed interest in the Philippines after a major improvement in the political relationship between the two countries."

One subject of increasing debate is whether the Chinese government will abandon its target of doubling its 2010 GDP by 2020 to become a high-income country by then.

This was one of the central aims of the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-20).

Wang, a state councilor on the Chinese State Council, or cabinet, who believes growth will remain about 6.5 percent next year, says targets play an important role in driving economic activity in China.

"The government mandate is to set objectives for people to reach, and therefore people are motivated. I think it is important that the government has set the overall objective to reach this target."

Chan at Credit Suisse says nothing is going to change until after the key party meeting in the autumn, but he believes there is more nuance in the goal set than is often perceived.

"Being a high-income society is actually a relative concept. By 2020 China might be a high-income society because other countries have not grown as quickly as it has over the previous decade. It will have achieved its objective without doubling GDP. It is not a discussion the government will have in 2017."

Chan believes that as the year begins, the main concerns will not be about the Chinese economy, as they were last year, but about other things.

"China’s real economy currently has less uncertainty surrounding it compared with many economies in the developed world right now. Last year there were discussions about whether China would significantly slow down. I don’t think that is so much an issue now." (By Andrew Moody)

■ There but for the presence of China…

Expert lauds country’s role as economic savior and as a guarantor of continued stability

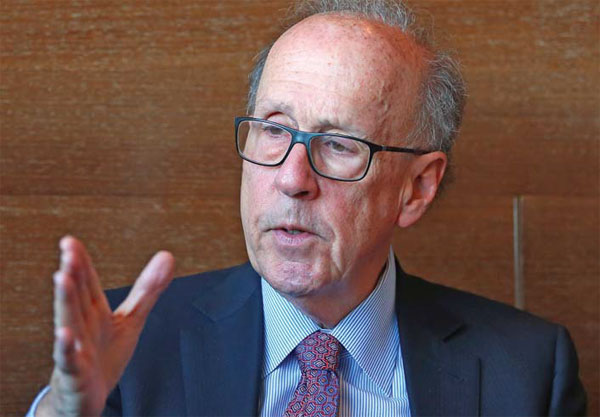

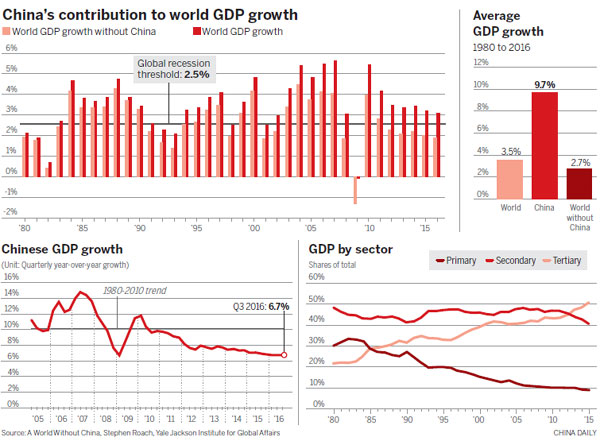

Stephen Roach, the senior fellow at the Jackson Institute for Global Affairs at Yale University, argues that world annual growth between 1980 and 2016 would have been just 2.7 percent – almost 25 percent less than its present 3.5 percent – without China growing at 9.7 percent during this period. Zou Hong / China Daily

The American economist Stephen Roach insists it is vital for the world economy that China continues to grow solidly in 2017.

The senior fellow at the Jackson Institute for Global Affairs at Yale University says that even with its "new normal" levels of growth its economy remains the engine of the world economy.

"If there is a dramatic slowdown in China there would be a period of weakness we have not seen at any period since the end of World War II," he warns.

Stephen Roach speaks at a lunch organized by the Center for China and Globalization (CCG), a think tank in Beijing.

Roach, also a former chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia, was speaking before giving a presentation on "A World Without China", looking at what would happen to the global economy without China’s economic momentum, at a lunch organized by the Center for China and Globalization (CCG), a think tank in Beijing.

In the talk at the Park Hyatt Hotel in Beijing, he argues that world annual growth between 1980 and 2016 would have been just 2.7 percent – almost 25 percent less than its present 3.5 percent – without China growing at 9.7 percent during this period.

And that if China’s growth was to fall from the 7.6 percent achieved in the first three quarters of 2016 to 5 percent next year, global growth would almost halve from 3.4 percent to 1.8 percent.

"Without China’s growth the world will have fallen into a very deep recession after the global financial crisis, and that would apply now," Roach says.

He argues that since 1945 the world has had a major growth engine with the US powering the world economy in the 1950s, Europe growing strongly for much of the period and Japan and South Korea emerging before China.

"If China is not there, I don’t think the US will provide it. I don’t think Europe will or the rest of Asia or the resource economies will. The world will enter a period of significant weakness."

Roach says that among the worst hit will be the European economies such as Spain, Greece and Italy, which already have high levels of unemployment.

"There has been a lot of structural unemployment since the end of the financial crisis, and the hope has been that rising global growth would be able to absorb that. This, however, will not happen in a world without China."

Roach, who was brought up in Beverly Hills, California, began his career as a research fellow at the Brookings Institution in the 1970s after his doctorate at New York University.

He then went on to work for the Federal Reserve before joining Morgan Stanley in the 1980s.

He first got to know China well in the immediate aftermath of the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s when he challenged himself to visit the country at least twice a month.

"For about five years I spent half my time there, and even now that I am teaching I still come four or five times a year."

Roach, who financially backed the Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton in the recent election, is skeptical as to how Donald Trump as president can follow a fiscal expansion strategy while erecting trade barriers against China.

He argues that the US would only be able to fund the resultant increased budget deficit with Chinese savings. US savings are 2.3 percent of GDP compared with China’s 40 percent.

"Fiscal expansion in a low-savings economy just spells bigger budget deficits and wider current account imbalances and trade deficits. This would put the US on a collision course with the protectionist policies that Mr Trump is also prescribing.

"Right now it is all blue sky and optimism (with the Dow Jones index hitting record highs in December) with little regard for some of the tougher issues which may be evident down the road."

Roach, also author of Unbalanced: The Codependency of America and China, fears the world situation is now worse than it was even in the inflationary era of the 1970s.

"It is hard to say from a geopolitical point of view but I think it is worse. You have the populist backlashes, the lack of appetite for trade liberalization and globalization.

"At the end of the 1970s we had high inflation, slowing growth, the specter of inflation but we worked our way through that by economic means rather than geostrategic cooperation."

Roach was encouraged by the Chinese government’s Central Economic Work Conference in December, which placed emphasis again on achieving "new normal" medium to high growth and supply-side reforms.

"China’s push toward supply-side reforms is welcome and important but it is not an excuse for not rebalancing the demand-side of the equation.

"What concerns me is that there is almost too much focus on the supply side without continuing to underscore the commitment toward consumer-led growth on the demand side. You need both supply and demand to drive China to the next phase and to avoid the middle-income trap."

Roach welcomes President Xi Jinping attending the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, next month and says it will be a chance for China to show leadership, if the West is seen to be retreating under Trump.

"They will want to hear that China is still committed to dealing with global issues from climate change to trade and also opening its markets and borders warmly to other nations."

He also believes much of the debate will be about the future of globalization, a concept almost led by China with its vital manufacturing role in global supply chains.

"Just where is globalization heading? There has been a lot of push-back against globalization; that is what Brexit was all about, that is what the ascendancy of Trump is all about and that is what potentially the election of Marine Le Pen in France is all about.

"These are some of the pressures that will be actively debated and discussed at Davos."

Roach argues, however, that as with 2016 there is still little sign of the world finally lifting itself from the global financial crisis.

"The theory of resilience of economic cycles is that economies in general are elastic organisms, so imagine holding a big rubber band. The further you pull it down, the faster it snaps back. We have had a very deep downturn but a very anemic snap back.

"There are still enormous headwinds in this post-crisis climate. If it had not been for China the world would be in a much weaker place." (By Andrew Moody)

From China Daily,2016-12-30